Have you ever wondered where the sites of famous paintings are actually located? This curiosity and the iconic Warrenheip Hills near Ballarat painted by Eugene von Guérard have led intrepid FedUni postgraduate researcher George Hook to make some fascinating discoveries. George tells his story here.

My thesis focuses on fidelity to nature issues in the paintings of leading nineteenth century Australian landscape painter Eugene von Guérard. In particular, I am interested in composite landscapes in which two field sketches are combined to form an artwork that communicates the essential nature of, or a narrative about, a specific environment.

In the National Gallery of Victoria hangs an iconic painting entitled Warrenheip Hills near Ballarat. As this important artwork is his first major Australian landscape painting it has received quite a lot of attention from art historians, von Guérard aficionados and locals, but rather puzzlingly the peak doesn’t look much like Mount Warrenheip nor has the idyllic rocky pool been located. My take on the painting was that most likely it is a composite work and the vantage point of the main source sketch might possibly be located if the painted shape of Mt. Warrenheip was ignored.

Eugene von Guérard: Warrenheip Hills near Ballarat 1854, National Gallery of Victoria.

My starting point was the artist’s large drawing in the State Library of Victoria. Assuming the distant hilltop visible between the trees is meant to be Mt. Warrenheip and the rocky pool is part of a creek flowing away from the viewer, then the trick would be to find a site somewhere along the Yarrowee River whose topography and hydrology matched that illustrated, with a view to Mt. Warrenheip thrown in. This proved easier said than done, especially given how extensively the Yarrowee River has been modified by miners, farmers, urban planners and the water board.

Eugene von Guérard: Warreneep hills bei Ballarat, 5th Februar 1854, State Library of Victoria.

More critical to locating the site were geological clues embedded in the drawing and painting, and here von Guérard had me fooled completely at times. In the drawing, the rocks forming the front edge of the pool are irregularly shaped but with a level top surface. Those in the painting have the polygonal shapes of tessellated basalt pavement, which is the top surface of highly regular columns of basalt lava.

My initial speculation about the geology was that the pool ledge could be a section of the front edge of a basalt lava flow from Clarkes Hill to the north, which has been gradually worn back by the tumbling action of water over geological time, but a misunderstood email from Federation University geologist Stephen Carey seemed to indicate there was no columnar basalt around Kirks or Pincott reservoirs, so I never bothered checking my initial conjecture.

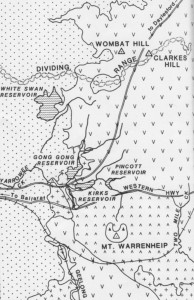

Lava flows and scoria cones east of Ballarat (detail from Figure 12-2.4 in Ian Clark, Barry Cook and Greg Cochrane, Victorian Geology Excursion Guide, Canberra, 1988, p. 202).

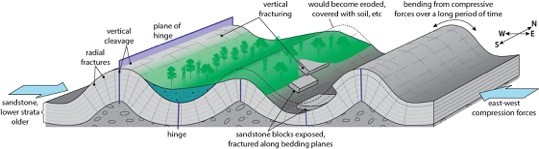

The blocky looking rocks forming the left bank above the pool in the drawing and painting are an intriguing feature as they don’t look much like basalt or even granite. David Taylor from the Geological Survey of Victoria thought they resembled vertically cleaved sandstone found only in the hinge of a fold. Due to tectonic forces in Earth’s crust, the sandstone bedrock underlying much of Ballarat has been crumpled into large folds running in a north-south direction. As fold hinges are usually only a few meters wide, they are relatively rare. If David’s insight was correct, then the key to locating the site would be to find where the Yarrowee cuts a hinge, matches the general topography of the drawing, and provides a view of Mt Warrenheip if taller trees were removed.

Tony Mander: Geology of folds in the Ballarat district.

Over a period of nine months, I investigated three sites along the Yarrowee and two on sandstone elsewhere, along the way acquiring some skill in using a machete and a geological hammer. I located two possible sites that met the above criteria, although one rather disconcertingly faced Blackhill rather than Mt. Warrenheip, but frustratingly neither Stephen nor David could find conclusive evidence of that elusive hinge at either site.

Over a somewhat subdued pub lunch at the Brownhill Tavern adjacent to one of my hopeful sites, I showed David a copy of the painting without realising that he had only ever looked at the drawing previously. He immediately picked up on the tessellated pavement and said there was columnar basalt in the catchment area east of the Ballarat-Daylesford Road. The next week I contacted Peter Field of Central Highlands Water, who gave permission to enter the catchment area between Kirks and Pincotts reservoirs. From topographic and geological maps, I worked out where the rocky pool ought to be if it still existed, and set out to walk from Kirks along the then dry creek bed to Pincotts, but the head-high blackberry proved impossible to penetrate, so I followed a logging track up to Pincotts and began to walk back down the creek.

Within minutes I stumbled across a rocky stream depression that matched so many of the topographical, hydrological and geological features in von Guerard’s drawing that I was immediately convinced I had found that site where he stood to make the sketch on which the famous painting is based. It was a thrilling moment realising that only he and I knew exactly where he had been sketching on the afternoon of the 5th of February 1854.

Site of the field drawing along the Yarrowee River

The rocky ledge just visible beneath the fallen tree trunk in the photo is indeed a knickpoint in a section of a columnar basalt lava flow, which has been steadily retreating upstream over the last three million years as tumbling water undermines the base of the ledge. The columns, however, are very irregular in shape so his tessellations must be attributed to artistic licence.

Since then I have taken several art historians to the site, or shown them photographic evidence, and all agree the evidence is strong, even compelling. Gordon Morrison, director of the Ballarat Art Gallery, said he would only be fully convinced if Mt. Warrenheip could be seen in the distance, so I enlisted the help of local photographer Andrew Thomas to fly his drone camera above the trees surrounding the now water-filled pool and below you can see the evidence that finally convinced him.

Andrew Thomas: View of Mt. Warrenheip from above von Guérard’s site when the pool was filled with water on 17 May 2015. (The fallen log can just be seen at the bottom middle. )

George Hook

August 2015