“Cast away all doubt suggested by reason [and pursue] a thorough belief in the assurance contained in the text and a faith in the spirit by which all prayers will be heard and answered.”

Rev. C Clarke of London, Dawson Street Baptist Church, Ballarat, June 1869

“Life needs something living to produce it; the beginning of life here on this earth must mean that there was life somewhere before. We are content.”

Rev. William Henderson, Presbyterian minister, Ballarat, 1882

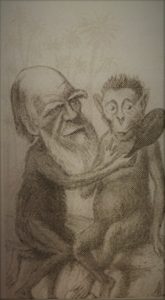

When Charles Darwin published the Origin of the Species in 1859 he had endured much self-doubt and personal torment over many years at the polarizing nature of his theory and its religious and spiritual implications.

Whilst not the first scientist to elaborate a theory of evolution or “transmutation” of species from a common origin, his Origin of the Species was unique for its readability and popularity with the public beyond the scientific community. Even hostile reviewers had to concede its “hosts of facts and charming diction”.

Many of us are familiar with the fall-out that followed its publication in London and on the world stage….but what was the response a little closer to home, in Melbourne and Ballarat?

Out of the frying pan and into the fire

For Australian society, Origin of the Species’ release came hot on the heels of the exciting free-for-all that was the gold rush and within a few short years of the formative and bloody conflict at Eureka. So, into a heightened mood of social turmoil, Darwin’s big idea added yet more grounds for doubt that threatened to chip away at the religious and social status quo.

Following a global trend, Australians were engaging with new ideas in the realm of spirituality and religion. Freethinkers’ and Spiritualist organizations were drawing in supporters. Amateur science was popular in a new mood of enquiry and popular education, spurred on by the building of schools, free libraries and mechanic’s institutes.

Members of the Ballarat District Book and Tract Society, in June 1869, bemoaned the influence of books of a “not only trashy, but..positively immoral nature being published at the present time.” They committed themselves to “the work of disseminating pure literature, especially among the young.”

When H.S. Earl, a famous American evangelist, visited Ballarat in 1865, 800-1000 people crowded the Mechanics’ Institute on Sturt Street to hear him speak. American spiritualists touting the wonders of mesmerism and séances, drew crowds hundreds-strong in regional centres like Bendigo and Castlemaine.

Newspapers of the day regularly advertised scientific exhibitions, lectures on geology, zoology, botany and astronomy and fossil-hunting expeditions.

When the Darwin controversy unfolded in Melbourne, the universities were the main players, but the topic drew commentary from all levels of society.

Sir Henry Barkley, then Governor of Victoria [1856-1863] chaired a public lecture on the question of evolution, whilst Frederick McCoy, head of the National Museum (today’s Melbourne Museum) procured three gorillas for the museum and emphasized “how infinitely remote the creature is from humanity”.

At the University of Melbourne, in July 1863, a professor of anatomy, George Halford, delivered a lecture entitled “The terminal divisions of the limbs of man and monkeys”. In this lecture Prof Halford set about trying to prove that there were significant osseous and muscular differences between the make-up of human feet and what he termed “the lower extremities of the monkey tribe”.

In the weeks following Halford’s lecture the evolution debate was the focus of leading articles and letters to the editor in both The Age and The Argus, with the two papers taking opposing positions on the question. The Argus made use of a favourite debating technique of pro-evolutionists by commenting that Halford “savours far more of the original gorilla than the improved anthropoid”.

Personal accusations flew back and forth between letter-writers and commentators, culminating in accusations that Professor Halford had turned on a visitor to his lab – “scalpel and forceps in hand” – believing him to be the writer of letters to The Argus under the pen name “Opifer”, which were scathingly critical of Halford.

It seems, reassuringly, that anonymous “key board warriors” and trolls are not solely recent phenomena of the online world. The Darwin debates provide evidence that bitter running battles in the Letters to the Editor pages were just as acrimonious – and anonymous to boot – 150 years ago!

The debate in Ballarat

Whilst in Melbourne the Darwin debate was very much a scientific one centred on the university, in Ballarat the debate went to the heart of concerns about God, man and morality with the debate firmly in the hands of church leaders and the religious.

The evolution question was thrust into the position of leading news in early and mid-1867 following a lecture on “The Philosophy of Creation”, delivered in February of that year in the Ballarat Mechanics’ Institute, by the visiting Reverend Alfred Henderson. The lecture, which seems to be an example of creationist geology was well-received and described as an “intellectual treat” by admirers, but when a local Reverend (another Reverend Henderson) of the St Andrew’s Presbyterian church, offered up a “mild protest on behalf of the Darwinian theory of the origin of the species” a passionate public debate was sparked.

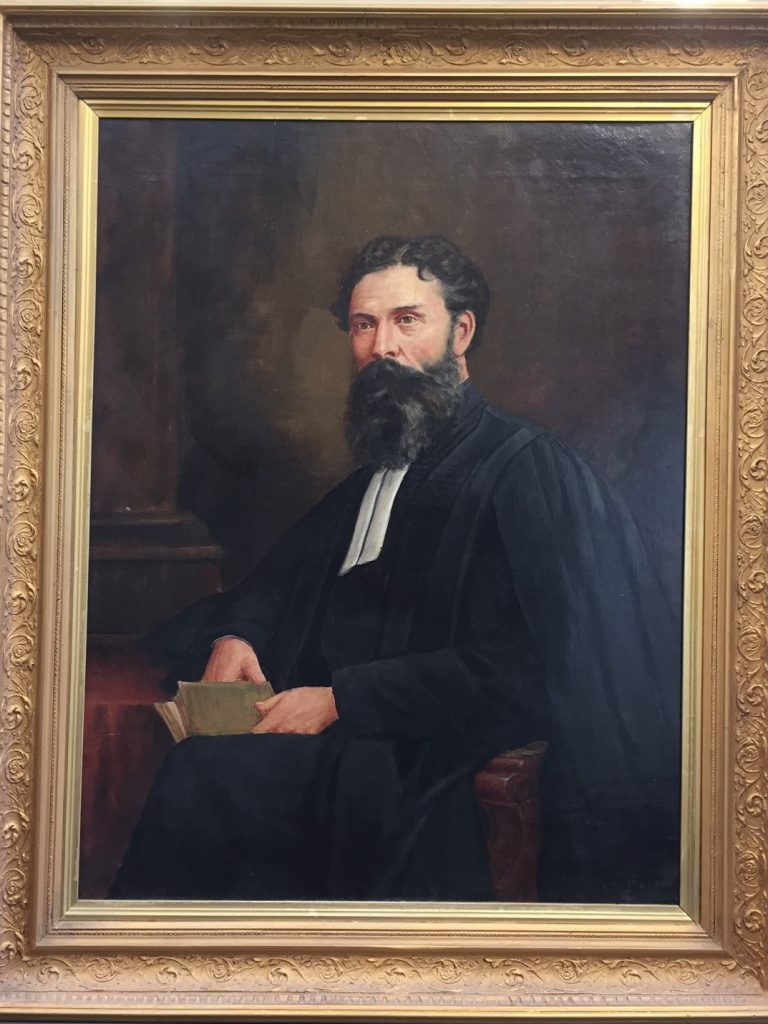

The second Reverend, a certain Rev William Henderson, argued that one’s acceptance or rejection of evolution theory had “nothing at all to do with a man’s Christianity or theology” and described Darwin’s theory as “beautiful but insufficient” giving evidence of God having worked ”according to order and by law” as opposed to the notion of ‘spasmodic’ creation.

The Reverend A. Henderson expressed astonishment that a fellow Christian minister would apply the term ‘spasmodic’ to the Divine operation and accused Rev W. Henderson of misrepresenting his arguments on Darwinism.

The lecture and Rev W. Henderson’s comments became leading news in the following day’s papers via Ballarat’s Evening Post, edited by Mr David Blair. Mr Blair took the opportunity to write a ‘letter to the Editor’ of the Evening Post (the editor being himself, though he does not say so) in which Reverend W. Henderson’s character and suitability as a Christian minister is called into question.

“..if Christian ministers are found openly avowing belief in Darwin’s theory, it is time to shut the Bible and close the Christian churches. Darwin’s theory and Christianity hold about the same relation to each other that darkness does to light and falsehood to truth” (David Blair, To the Editor of the Evening Post, 27 February 1867)

Mr Blair challenged Rev Hendersen to “a friendly public discussion” of the subject in which he hoped to prove Darwin’s theory “first, unscientific, secondly, unscriptural; and thirdly distinctly atheistical”.

Anglicus vs. Publicus

In the following days two more Ballarat residents put forward their opinions on the subject. Both residents chose to write under pseudonyms, with ‘Anglicus’ writing to The Evening Post to concur with David Blair, and ‘Publicus’ writing in support of Reverend Henderson to The Ballarat Star.

On March 1, Anglicus outlines how the Rev W. Henderson’s comments at the lecture in question “marred” the proceedings and amounted to “nothing short of rationalism”. He asks :

“Would the Reverend have humanity acknowledge our ancient lineage from mammoths and mastodons and be haunted by the baleful shadows of extinct monsters?”

The next day David Blair again writes a letter to his own paper, impatient at the fact that Reverend Henderson has not responded to the challenge of “ a friendly public discussion of the subject” made in late February.

Publicus then responds beginning what is to be a recurring and bitter debate directly between himself and David Blair. Publicus writes with an implicit familiarity with Mr Blair, suggesting an animosity that pre-dates the Darwin debate. He refers to David Blair as “a person of so dilapidated a reputation”, ridiculing Blair’s “sensational appearances as a letter-writer to his own paper”. As an “occasional hearer” of the Reverend W. Henderson he defends the Reverend’s reputation, listing off his many virtues as a Christian minister, and finishes by describing Blair as proof of the Darwinian hypothesis by being “a new and singularly repulsive species of the old disreputable genus humbug”.

After several months of silence in the Ballarat papers on the question of evolution, David Blair held a lecture for the Young Men’s Christian Assocation in the Mechanic’s Institute entitled “Darwin’s Theory Exposed and Refuted”.

In another exercise in anonymous editorializing, Blair dedicated the leading news column of The Evening Post of the following day to an account of his lecture of the night before. He describes it as attended by “a very intelligent and respectable audience”. He returns to the question of the Reverend Henderson’s silence regarding a public discussion of Darwin’s theory and suggests that the Reverend lacks the courage to debate him. He criticizes “the anonymous slanderous personal attacks” by Publicus and refers to The Ballarat Star as a “disreputable Ballarat paper”. Blair claims to know perfectly well who Publicus is and suggests that at the repetition of his lecture on Darwin he “may take the occasion to unmask this stabber in the dark” to force him to defend his “athetistical principles, on the public platform”.

“In Ballarat it is to be held a crime against society for any man to stand up and avow his belief in the plain teachings of the Bible and the common faith of all Christians. In Ballarat a man’s personal reputation shall be assailed in the public journals by coward hands wearing the mask of the anonymous, if he dares publicly to express his dissent from the brutalizing doctrines of atheistical science, falsely so-called.”

Publicus responds to David Blair in two more lengthy letters to the The Ballarat Star. Again, Publicus provides great detail of the ways in which he believes David Blair to be a prime example of the evolutionary hypothesis: “Here we have a lecturer-cum-editor absolutely and incontrovertibly sui generis”.

“Mr Blair says I must refute all the writers he quotes before I must say I think Darwin and his disciples (of whom I have distinctly said I am not one) may not be atheists. Well, I am a protestant. Must I, then, refute the Pope and all the papists in Christendom? Mr Blair is a Presbyterian. Has he refuted all the Episcopalians, and all the Wesleyans, Congregationalists, &c?”

In Ballarat and Melbourne the Darwin debates drew out some of the differences between the two cities. A rising university-based intellectual elite in Melbourne had come to replace the cities’ religious leaders as authorities on this question. In Ballarat the debate encapsulated the continued centrality of church and religion in all matters of social importance.

Helen Hunter is a historian and researcher based at Federation University Australia’s Centre for eResearch and Digital Innovation (CeRDI). For further information on this topic email h.hunter@federation.edu.au