Helen Hunter reflects on the ever-steady presence of a memorial tree in the years following conflict

It is nearly 40 degrees Celsius on the morning I decide to pay a visit to my grandfather’s commemorative tree on the Ballarat Avenue of Honour. Wandering in the dry and narrow roadside strip (the space somewhat lacking no doubt as the Avenue was originally laid for horse and buggy) I am sweating, scorched by the sun that’s barely filtered by the avenue’s trees.

I have proudly arrived to not only connect with the tree I’ve not visited in perhaps 20 years, but also to run my own personal test of the mapping feature found on the City of Ballarat Honouring Our Anzacs website. The website’s fantastic pin-point mapping of my grandfather’s tree has informed me of the location of his tree among the 22 kilometre stretch of elms, American Ash and English Ash. It also informs me of the tree number (“3027”), tree species (“Ulmus Sp.”) and perhaps most excitingly of all, the name of the E.Lucas & Co. employee who planted the tree (a certain Miss E. Pitts).

Ballarat’s E.Lucas & Co. textile company, under the leadership of dynamic sales manager Tilly Thompson, famously rallied its staff of 450 young seamstresses to fundraise and plant out the entire avenue of trees. Planting was carried out from June 1917 in eight rounds, with the assistance of the Boy Scouts, oversight by professional gardeners and carpenters to install the tree guards, as well as plantings carried out by visiting dignitaries.

Before today, my regular trips along the Avenue to visit a friend were coloured by the anxious and somewhat guilty feeling of knowing that I couldn’t locate my beloved Pa’s tree.

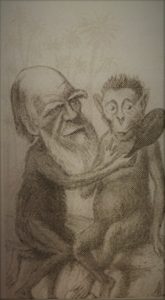

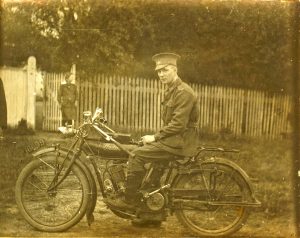

My grandfather, Alexander Hunter, left his family home in Buninyong in September 1917, aged 18, to enlist in the war. Over the years I’ve seen many sepia-toned photographs of my grandfather in uniform. I’ve scratched the surface of the story, patched together romantic notions, assumptions and snippets of information based on hazy memories of sitting down to dinner with my grandfather as a child. But today’s visit to the tree represents me truly deciding to take stock of his story – to take the time to see his tree as a precursor to learning more of what he went through and saw while he was at war.

As I navigate the long Avenue searching for his tree the heat radiating from the tar is blistering and I imagine a pleasant and slower-paced setting 100 years ago when it was planted. I remind myself that these few minutes staggering roadside in a sweat hardly compares to the privations any one of these soldiers, paid tribute to by the surrounding trees, would have gone through. For that matter even Miss E Pitts herself would have likely endured more hardship than I, weathering the elements in the winter of 1918 to voluntarily dig and plant my grandfather’s tree.

I have read that such loving care was taken in the preparation for tree planting by the Lucas Girls that one of the soldier’s family members was personally invited to attend the planting alongside a member of the Lucas and Co. staff. The Star reported during the first round of tree plantings in 1917:

A personal letter has been sent by the young lady who is to plant the tree to the next of kin of each soldier, requesting their presence and assistance.

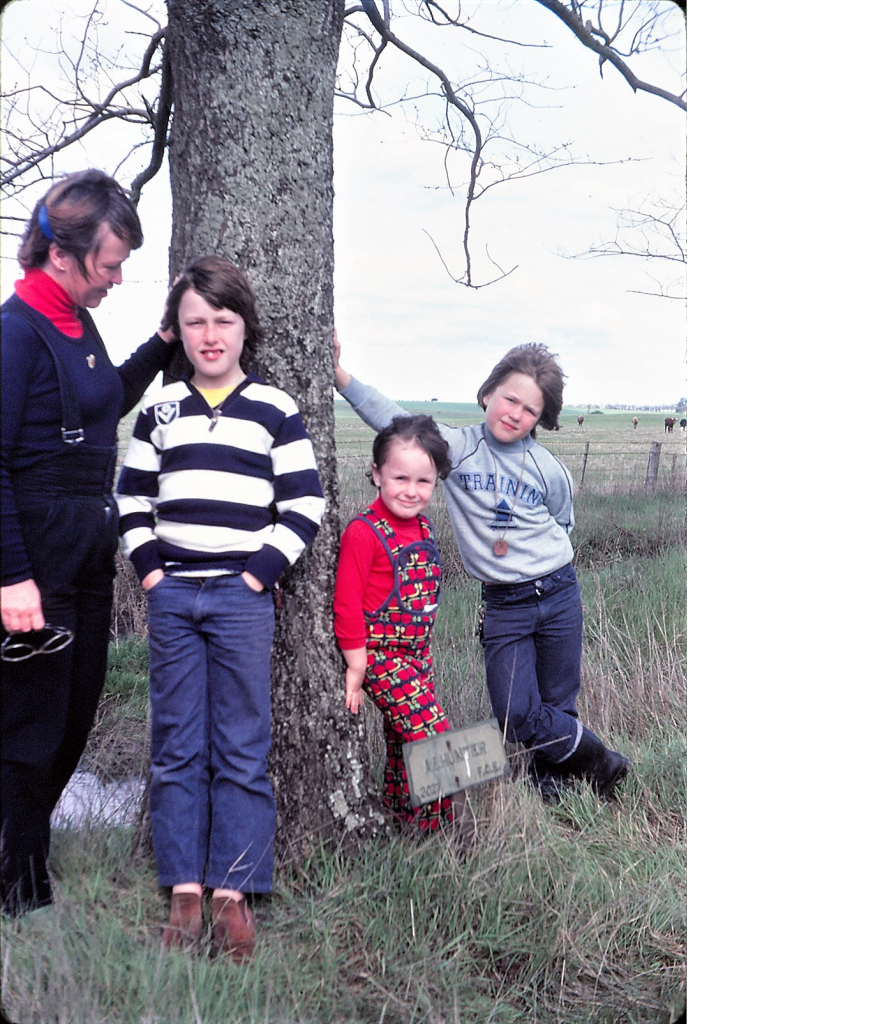

I have a memory of visiting the tree as a young girl, pulling in to the side of the road on the Avenue of Honour, on one of many lengthy family road trips. Fields stretching in the distance either side of the avenue.

We bundled out of the car to see ‘Pa’s tree’, a silent sturdy symbol of his participation in a war that was but a fairy tale to me.

We gathered around the tree for a family photo and proudly took in our grandfather’s initials and surname set into the bronze commemorative plaque at the tree’s foot.

My grandfather at the time was in his early eighties and living in Donald in the Wimmera, a retired mechanic. Following the war he returned to Australia in late 1919. From the age of 20 he spent some seven years farming on land owned by his family in Scotsburn, unable (or unwilling) to work inside following the long stretch of time abroad, wandering in the outdoors and sleeping in rough accommodation.

I recall a visit to his tree in my early twenties which came with a much fuller understanding of the war he took part in. Having studied trench warfare in World War I at university, my thoughts now ran to the true horrors of war – the long lists of dead, the drawn out stand-stills inherent to trench warfare, fraternisation between enemy troops, followed by the brutal self-sacrifice of surprise offensives. I wonder at just how much my grandfather actually saw.

I cross the road and begin scanning the plaques of the trees, realising happily that the numbers are steadily approaching “3027”. I see the tree of Frank Penhalluriack, a distinctive surname I remember well as belonging to family friends of my grandfather. And then two trees down I am finally at Pa’s tree: AE Hunter, 2nd FCE (2nd Field Company Engineers).

I take in the fields running behind his tree and am pleased to realise that the tree itself is likely the original planted 100 years ago. A full century has elapsed since my grandfather took the journey alongside so many other young men, into an unknown battle that was more protracted and horrific than any of them could have foreseen. I struggle to realise that the man I knew was really, when this happened, but a boy just out of his teen years. Boys of the same age today would be, mercifully, focussed on beginning summer jobs, playing their X-Box or making plans for university, not engaged in a conflict they barely had the life experience to understand let alone give their lives and the lives of others for.

The tree, for our family, has been a spot to stop by over the years, to think about the man we loved and admired so much, and to feel a connection to those days so long gone but so influential on the families, towns and people we know today. Today, while my grandfather’s grave may be many hour’s drive away this simple tree is not so far and is a touch point to his and our past.

Do you have a relative or family friend who enlisted for war in Ballarat or Ballarat East? Do you visit their tree or are you perhaps curious to locate their tree for the first time? A complete database of the 3,801 Ballarat men and women who served in World War One is accessible on the Honouring Our Anzacs website, where you can retrieve a serviceperson’s biography in brief, their commemorative tree number and a map of its location.

We would love to hear your stories of visits to Ballarat’s Avenue of Honour and what it means to you. Please share your pictures or memories in the comments. If you have a longer piece you would like to contribute to the HUL blog please email Helen Hunter on h.hunter@federation.edu.au

Helen Hunter is a historian and researcher based at Federation University Australia’s Centre for eResearch and Digital Innovation (CeRDI).